Most people think mindset changes when you start thinking differently. When you adopt better beliefs, become more positive, or motivate yourself enough to act. In practice, that rarely works for long.

Your mindset doesn’t show up in calm moments or reflection alone. It shows up under pressure – when something is at stake and you react automatically. In those moments, you’re not choosing what to believe. You’re interpreting what’s happening, and that interpretation makes certain actions feel reasonable and others impossible.

This article lays out a practical, step-by-step method for doing exactly that – by working with the situations where your mindset already reveals itself and changing how you interpret and respond to them over time.

Why changing mindset is harder than it sounds

Changing your mindset is possible. With training and the right approach, it can be improved. What’s often underestimated is how difficult it is to do in practice.

Your mindset operates largely outside conscious awareness. It shapes how you interpret situations and how you respond to them, long before you have time to think things through. Because of that, most of what your mindset produces feels like the truth, or simply “who you are”, rather than something you’re actively doing.

That’s what makes mindset change hard. You’re not just adding new ideas. You’re challenging interpretations that have been reinforced over time and replacing them gradually. This doesn’t happen through insight alone. It requires consistent exposure, deliberate action, and a system that works under real conditions.

Your mindset doesn’t feel like something you’re doing. It feels like the truth – or simply who you are

What a mindset actually is

Your mindset shapes how you interpret what happens to you and how you respond to it. It influences how you see yourself, how you relate to others, and how you make sense of both internal experiences and external events.

Because these interpretations guide your actions, they gradually shape your reality. Over time, they can either support growth and responsibility or reinforce avoidance and limitation.

To work with your mindset in practice, it helps to understand what it’s actually made of. Two mechanisms matter here. Together, they form the foundation for changing how it operates.

Mindset is interpretation, not belief

At its core, mindset is about interpretation. It’s how you make sense of what happens – internally and externally – and what that meaning tells about you, others, and what’s possible.

Internally, this includes how you interpret your abilities, your potential, what you deserve, and what you think you can or can’t do. Externally, it shapes how you interpret opportunities, setbacks, responsibility, and how others treat you.

These interpretations form a blueprint for your reality. Once that blueprint is in place, two things tend to happen:

You act in ways that confirm it.

The actions that feel reasonable to you are filtered through your interpretation – whether that pushes you forward or holds you back.

You notice and interpret information selectively.

You pay more attention to what supports your existing view and reinterpret conflicting information in ways that preserve it.

Over time, this creates stability. A supportive interpretation encourages responsibility, effort, and engagement. A limiting one encourages avoidance, self-protection, or blame. Both persist unless something interrupts the loop.

How action reinforces your mindset

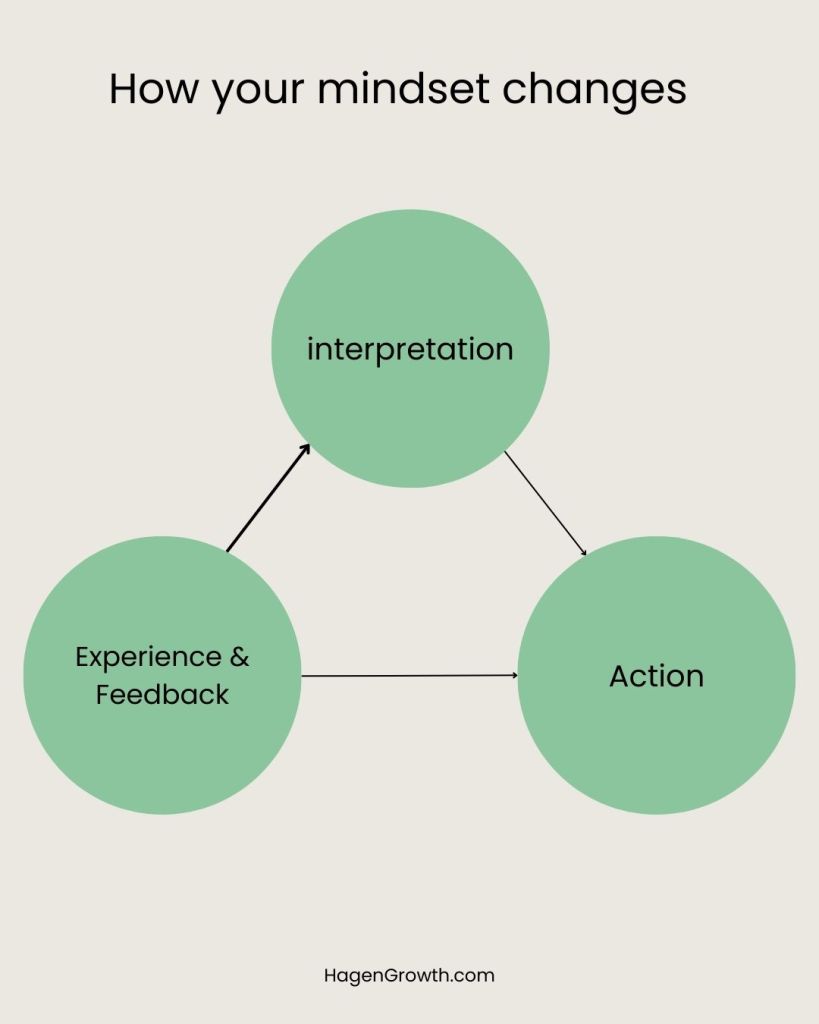

A mindset isn’t static. It shifts over time as a result of experience. For some people, that shift is small. For others, it’s dramatic. The difference is rarely explained by circumstances alone.

One of the strongest drivers of mindset change is something within your control: your actions. Every time you act, you reinforce a way of interpreting the world. Whether it’s avoiding something, engaging with it, or repeating a familiar behavior, your actions teach your nervous system what is normal and what is possible.

Over time, this is how a mindset stabilizes or changes. Action doesn’t just express your mindset – it actively shapes it. This relationship between interpretation and action is the foundation of the mindset training loop.

Summary: What a mindset actually is

- Mindset is how you interpret situations, not the beliefs you claim to hold.

- Those interpretations shape what actions feel reasonable or impossible.

- Repeated action reinforces interpretation over time.

- Mindset changes through experience, not insight alone.

The mindset training loop – how to change your mindset in 6 steps

Changing your mindset is possible, but without a structured approach it often leads to frustration. The mindset training loop is a simple framework built around six repeatable steps that make mindset change practical.

The loop isn’t designed to create sudden change. One pass rarely replaces an old mindset. What it does is move your interpretations slightly in a better direction each time you apply it. Repeated over different situations and over time, those small shifts accumulate.

Because the loop is repeatable, it’s also resilient. If you fall back into old patterns, you don’t start over from nothing – you return to a structure you already know how to use. That’s what makes mindset change maintainable.

Related: Create personal growth with the Hagen Growth Loop

Step 1: Choose one recurring situation that triggers friction

If you already have a mindset you want to work on, it might seem natural to try to change it directly. That usually doesn’t work. Mindsets don’t change in isolation – they show up in specific situations. That’s where you need to start.

If you’re not sure which mindset to challenge yet, that’s fine. Instead of looking for a mindset, look for friction. Find a situation that regularly creates tension, hesitation, discomfort, or avoidance and use that as your entry point. The mindset will reveal itself through how you interpret and respond to it.

This step is simple. Identify one recurring situation where friction shows up. Nothing more. You don’t need to analyze it yet or try to change anything. Just choose the situation.

What counts as a good situation

While your mindset is active in every situation, not all situations are useful as a starting point. A good situation for mindset work usually has three characteristics.

- It creates friction – The situation triggers some form of resistance – doubt, hesitation, frustration, shame, or avoidance. If nothing feels at stake, there’s nothing meaningful to work with.

- It’s noticeable – You need to be able to observe what’s happening internally as the situation unfolds. If the reaction is too subtle or unconscious to notice, it’s difficult to examine or change.

- It’s frequent – The situation needs to occur often enough that you can see patterns and track change over time. Situations that happen rarely, randomly, or are fully outside your control are poor starting points.

A useful situation has all three. If one is missing, the process becomes vague or unreliable. Take some time to identify a situation in your life that fits these criteria before moving on.

Common mistakes

The most common problems at this stage come from choosing the wrong kind of situation.

- Picking a situation that’s too rare or too specific – If the situation doesn’t happen often enough, you won’t get reliable feedback. Reflections will be dominated by noise rather than patterns, making it hard to tell whether anything is actually changing.

- Picking a situation that’s too broad – “Work” or “relationships” are not situations. They contain too many different triggers and interpretations at once. Narrow your focus – for example, how you start your workday, how you behave in meetings, or how you respond to new responsibilities.

- Picking more than one situation at a time – Working on multiple situations increases complexity and cognitive load. That makes consistency harder, and without consistency, mindset change doesn’t happen.

Choosing a single, well-defined situation keeps the process simple enough to sustain – which is crucial for change.

Step 2: Identify your current interpretation

Once you’ve identified a situation that creates friction, the next step is to make your current interpretation explicit. How are you making sense of what’s happening – and what does that meaning imply about you, others, or what’s possible?

At this stage, you’re not trying to change anything. You’re only observing. Notice what the situation seems to tell you, what it pushes you toward or away from, and how it affects your behavior. The goal is to see the interpretation that’s already running.

How interpretations hide as “facts”

You’ve lived with your mindset for a long time. Because of that, the interpretations it produces usually feel like facts. They’re familiar, automatic, and rarely questioned.

That’s why they’re easy to miss. Interpretations don’t show up as opinions, but present themselves as reality. And unless you slow down and deliberately surface them, they’ll continue to run unnoticed.

Simple prompts to surface them

Especially in the beginning, it can be difficult to see your interpretation clearly. These prompts are designed to surface what’s already running beneath the surface. Answer them slowly and honestly – the clearer you get here, the easier the next steps become.

- What does this situation seem to mean right now?

- What am I assuming about myself, others, or the outcome?

- If I had to state my reaction as a sentence, what would it be?

- What does this interpretation make me want to avoid or protect?

- If I follow this interpretation, what is the next obvious action?

Interpretations rarely announce themselves as opinions. They present themselves as reality

Step 3: Define a functional replacement interpretation

Once you’ve made your current interpretation explicit, the next step is to define a replacement. This is the interpretation you’ll be training instead.

It won’t replace the old one immediately. At first, it will feel weaker, less automatic, and easier to lose under pressure. That’s expected. The goal here isn’t instant change, but to define a direction – an interpretation you can reinforce through repeated action.

As that interpretation becomes easier to access in one situation, it begins to influence how you interpret similar situations as well. That’s how broader mindset change starts.

What makes an interpretation usable

Not every new interpretation is useful. Replacing a negative interpretation with a different but equally limiting one leads to the same outcome. Even interpretations that feel good in the moment can be harmful if they remove responsibility or distort reality.

A usable replacement interpretation has a few key characteristics:

- It supports growth without denial – It allows improvement through effort, without promising guaranteed outcomes.

- It reduces shame without removing accountability – It doesn’t punish you for trying, but it also doesn’t excuse avoidance or disengagement.

- It treats ability as trainable, not fixed – Difficulty is seen as part of the process, not evidence of a permanent limit.

If your new interpretation moves you away from avoidance, self-blame, or fixed conclusions – and toward engagement and responsibility – it’s usable. It doesn’t need to feel fully true yet. Integration takes time. The goal is not to replace everything at once, but to shift the direction you’re moving in.

A usable interpretation doesn’t need to feel fully true yet. It needs to move you away from avoidance and toward engagement

Why positivity usually fails here

A common replacement people reach for is positivity – the idea that if you think positively enough, things will work out.

There’s some truth to this, but on its own it usually fails. Positivity without realism drifts into over-optimism. It feels good in the moment, but it removes the need to engage with difficulty, effort, and feedback. That’s why it often leads to stagnation rather than change.

A more workable alternative is positive realism. It keeps the assumption that growth is possible, but pairs it with effort, systems, and responsibility. Outcomes aren’t guaranteed, but improvement is treated as something you actively participate in. That’s what makes an interpretation trainable rather than fragile.

Step 4: Attach a small daily action

Once you’ve defined a new interpretation, it won’t change anything on its own. It has to be reinforced in real situations. That’s where action comes in.

The role of the daily action is simple: to make the new interpretation lived, not just understood. Each time you act in line with it, you give your nervous system evidence that this way of interpreting the situation works.

Sometimes the action happens directly inside the triggering situation – you respond differently in the moment. More often, it sits slightly adjacent: a small, repeatable behavior that shapes how you show up when the situation occurs. Over time, that shift makes the new interpretation easier to access.

Related: How to build better habits

Criteria for the action

Not every action will be effective. What works depends on the situation and the interpretation you’re trying to train. To choose an action that actually changes your mindset, it helps to follow these criteria:

The action only makes sense if the new interpretation is true

If the action fits just as well under the old interpretation, it won’t shift anything. For example, if you’re training yourself to see failure as information rather than something final, asking one clarifying question about what went wrong supports that interpretation. Telling yourself to “try harder” does not.

It creates mild friction, but not avoidance

The action should feel slightly uncomfortable. If it feels completely safe, it won’t change anything. If it’s too demanding, you won’t repeat it. The goal is a sustainable level of discomfort that you can maintain over time.

It’s small enough to repeat daily

Mindset changes through frequency, not intensity. A small action done every day is far more effective than a demanding one done occasionally.

It has a clear yes-or-no outcome

You should be able to answer clearly whether you did the action or not. Vague actions like “be more open” invite rationalization. Concrete actions like “talk to one new person” don’t.

It happens in the real situation

The action needs to meet the situation where the interpretation normally shows up, with the same pressure and emotion. Reflection and journaling are useful, but they support the loop – they don’t replace the action.

It works even on low-energy days

If the action only works under ideal conditions, it won’t change anything. Real consistency requires actions that survive fatigue, stress, and imperfect days.

If the action feels optional, cosmetic, or disconnected from the situation, it won’t change your mindset – even if it feels productive.

Insight explains your mindset. Action is what updates it

Why insight without action does not change your mindset

Your mindset is shaped by accumulated experience. Over time, it updates based on what you do – how you act, what you avoid, and what you repeat. That’s why understanding something without acting on it doesn’t change how you feel or respond. The interpretations built through years of behavior are stronger than intention alone.

Action is what provides proof. Each time you act in a new way, you create evidence that a different interpretation is possible. That’s how your mindset updates through repeated confirmation in real situations.

Step 5: Run the loop for one short cycle

Once you’ve defined the action, it’s time to run it for a short cycle. The exact length can vary, but a seven-day cycle works well in most cases. During this time, the action is repeated every day.

Your focus in this cycle is simple: do the action consistently. Don’t reduce it because it feels uncomfortable or skip it because you’re tired. If the action regularly feels impossible to complete, that’s usually a sign it didn’t meet the criteria in the previous step and needs to be adjusted.

You may notice changes or insights along the way. That’s fine. Make a brief note and move on. The purpose of this loop isn’t analysis, but repetition. Reflection comes later.

What changes quickly

Early in the cycle, you may start to notice small changes. The situation can feel slightly easier to engage with, friction may decrease, and the action may begin to feel more natural. On good days, the new interpretation might show up more quickly or with less effort.

These early shifts are usually the result of exposure. Repeatedly acting in the situation reduces uncertainty and makes the response less novel. That doesn’t mean the interpretation has changed yet – it means the system is beginning to adapt.

These changes are fragile at first and need to be maintained through repetition to become stable. Even small shifts matter. They create the conditions for longer-term change and make continued engagement possible.

What takes longer

Lasting change takes longer. While early progress often comes from exposure, how you respond to negative feedback is usually the deeper challenge. This is where old interpretations tend to resurface and where avoidance feels most tempting.

Negative feedback often triggers the same interpretations you’re trying to change. When that happens, it can feel like regression. But this isn’t a sign the process isn’t working – it’s the point at which the mindset is actually being tested.

When old interpretations resurface, that isn’t failure. It’s the point where the mindset is actually being tested

Progress in this phase is uneven. Some days will feel easier, others harder. What matters isn’t the absence of setbacks, but whether you continue to act despite them. Over time, repeated engagement under less favorable conditions is what stabilizes the new interpretation.

Step 6: Review and adjust

After completing a short cycle, it’s time to review and adjust. This step has two purposes: to assess whether the action was executed consistently, and to see whether your interpretation shifted as a result.

Start by reviewing the cycle itself. Did you do the action consistently? When the situation came up, did your interpretation change at all – even briefly or inconsistently?

Based on that review, you have two options: either repeat the loop to strengthen the new interpretation, or adjust the interpretation or action and begin a new cycle.

Whatever the outcome, treat it as usable information. If the loop worked, you have a signal worth reinforcing. If it didn’t, you now know what needs to change. Either way, the process continues.

Reflection questions

How effective your adjustments are depends on how clearly you reflect. These questions are meant to review how the loop actually worked – not to judge progress or draw conclusions about yourself, but to decide how to run the next cycle more precisely.

- In which moments did the old interpretation show up automatically?

Look for patterns. Specific situations, pressures, or triggers. - In which moments did the new interpretation hold?

Note when it appeared without forcing, even briefly. - What did I do differently when the new interpretation held?

This helps confirm whether the action and interpretation were actually linked. - Did the daily action feel connected to the situation when it mattered?

If not, the action may have been too symbolic or too indirect. - On low-energy or high-pressure days, did the action still happen?

This tests whether the loop works under real conditions. - What made the new interpretation easier or harder to access?

Environment, timing, context, or people often matter more than effort. - What should stay the same in the next cycle — and what should change?

Adjust the situation, the interpretation, or the action, but avoid changing everything at once.

Learn more about how to journal here

When to keep vs. change the loop

Sometimes the right move is to repeat the loop. Other times, it’s better to change it. The decision depends on what your review shows.

When to keep the loop:

Keep the loop if the cycle moved you in the right direction, but the new interpretation hasn’t stabilized yet. This is the most common outcome. Even when the action is well chosen, it usually takes multiple cycles before the old interpretation loses its grip.

When to change the loop:

There are two cases where changing the loop makes sense:

- If your reflection shows that the action didn’t have the intended effect, or the situation no longer feels relevant. In that case, revisit the interpretation or action and try a different approach.

- If the new interpretation has largely replaced the old one in that situation. Here, it can be useful to maintain the action at a lower intensity while restarting the loop with a new situation.

In both cases, the outcome is usable. Completing a full cycle gives you information you didn’t have before, and that information is what allows the process to continue.

Summary: The mindset training loop

- Start with real situations where friction shows up.

- Define and train interpretations through small, repeatable actions.

- Repetition matters more than intensity or insight.

- Review and adjust the loop to strengthen what works over time.

Reapplying the method in other areas

The mindset training loop is not limited to a specific area of life. It can be applied anywhere a mindset shows up in repeated situations.

What changes across domains is not the method itself, but the inputs. The situation you work with, the interpretation you challenge, and the action you attach will differ. The structure of the loop remains the same. The six steps remain the same. And the way change unfolds tends to follow the same pattern.

In training

Situation:

A friend of mine enjoys working out, but whenever he doesn’t have time for a full session, he skips training altogether. Over time, this leads to many missed workouts.

Interpretation:

He interprets shorter workouts as not being good enough. If he can’t do his full routine, he sees the session as a failure and assumes that doing a reduced version somehow “doesn’t count.”

Action:

To challenge this all-or-nothing interpretation, he commits to doing a minimum viable workout whenever time is limited. If he only has 15 minutes, he trains for 15 minutes.

By repeatedly acting on this interpretation – that some training is better than none – he weakens the belief that workouts must be perfect to be worthwhile. Over time, this shifts his mindset from perfection to consistency, which produces far better long-term results than waiting for ideal conditions.

In relationships

Situation:

When I was younger, I struggled to express even small preferences. When asked what I wanted to eat, watch, or do, I would freeze and default to “I don’t know – what do you want?”

Interpretation:

I interpreted sharing my opinions as risky. I assumed others would judge my preferences as strange or wrong, and that showing them would make people pull away.

Action:

Each day, I had to state my genuine preference in at least one low-stakes situation – what to eat, watch, listen to, or spend time on – without deflecting or letting others decide for me.

Repeated exposure showed me that expressing preferences didn’t lead to rejection. Over time, the interpretation shifted from “having opinions pushes people away” to “having preferences is normal and safe.” That change made it easier to speak up and stand by what I wanted.

In work

Situation:

When I started my first office job, I stayed silent during meetings. Even when I had relevant thoughts or disagreed with something, I stayed silent.

Interpretation:

I interpreted speaking up as risky. I believed that if I said something wrong, it would expose that I didn’t belong in the room. I assumed I needed to be “right” before I was allowed to contribute.

Action:

In every meeting, I committed to saying one thing. It could be as simple as agreeing with someone else, asking a clarifying question, or sharing a short point of my own. The only rule was that I had to contribute once in every meeting.

Repeated exposure weakened the belief that mistakes would have serious consequences. Over time, the interpretation shifted from “I must be right to speak” to “participation is part of doing the job.” As that interpretation changed, speaking up became easier and more natural.

Mindset as a trainable skill

Mindset is a trainable skill. The one you have today was formed through past experiences, repeated interpretations, and the actions that followed from them. Because it has developed over time, it can feel deeply personal, even fixed – but it isn’t.

Like any other skill, mindset can be trained with the right approach. It’s complex and influenced by many factors, but it still responds to structured effort. By deliberately running the mindset training loop, you challenge how you currently interpret situations and gradually replace unhelpful patterns with more functional ones.

One loop won’t undo every limiting interpretation you’ve built over years. But it will move you in the right direction. With enough repetitions, those small shifts compound. Over time, a mindset that once limited your behavior becomes one that supports growth instead.

That’s the key: mindset doesn’t change through insight alone – it changes through training. Run the loop consistently, and let the results speak for themselves.

What to read about next

- Mindset and Discipline: The Foundation of Sustainable Change - March 4, 2026

- Thinking Vs. Reflection – What is the difference? - February 20, 2026

- Why we do things we later regret – and how to interrupt the pattern - February 13, 2026