Everything on Hagen Growth starts here – the mindset, the habits, and the systems that turn ideas into change. For years, the philosophy behind Hagen Growth existed only in fragments – shaped by experience but never written down. This page brings it together. Here you’ll find the core ideas that explain how lasting growth happens and how to build it yourself. Each section links to deeper guides if you want to explore further.

This is for you if you know what you should be doing — but struggle to do it consistently

You’ve read the advice, understood some principles, and likely tried different approaches. What’s missing isn’t information or motivation, but structure, alignment, and a way to turn intention into steady action. Hagen Growth is built around small, deliberate steps that reshape identity over time – not quick fixes or rigid systems, but a sustainable approach to growth.

Key points: The Hagen Growth Philosophy

- Positive Realism: True growth requires accepting reality exactly as it is, while applying the structured effort needed to improve it.

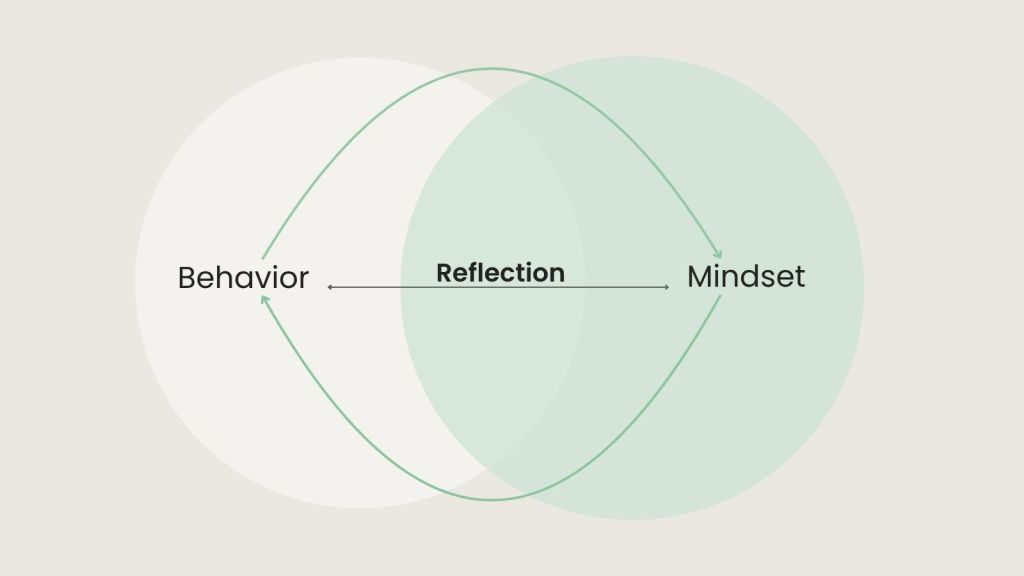

- The Hagen Growth Loop: Your mindset and behaviors constantly shape each other. Deliberate reflection is how you take control of that loop.

- Systems Over Motivation: Motivation is unreliable and discipline has limits. Sustainable progress relies on systems, routines, and small wins.

- Identity Change: Growth begins as deliberate, conscious effort, but the ultimate goal is for those actions to become your natural identity.

Change isn’t a sudden breakthrough. It is the result of continuous, deliberate alignment between how you think and what you do.

Positive realism – the foundation of Hagen Growth

In 8th grade, my grades were so low that my counselor told me I probably wouldn’t finish school. Vocational training was the only option. Then, at the start of 9th grade, one teacher changed everything. She sat me down and told me something no one had ever said before: that I wasn’t broken, I just hadn’t learned how to work yet. That with hard work and consistent effort, I could do much more.

That year, I went from nearly failing to graduating with some of the best grades in my class. She taught me that effort can reshape any ability, that we aren’t fixed beings, but always able to evolve.

I didn’t have the words for it back then, but that belief is what I now call positive realism – the foundation of Hagen Growth.

Positive realism combines two separate concepts into one.

Realism means seeing the world as it is – understanding what’s likely, what’s possible, and what it takes to get there.

Positivity means believing that growth and progress are always within reach – that effort, alignment, and patience can move almost anything forward.

Together they form a mindset where optimism meets structure. Positive realism says most things are possible under the right conditions. The positive brings intent, the realism builds the conditions: systems, effort, and time. Without this balance, we either drift into blind optimism, expecting progress without effort, or sink into realism so rigid that we stop trying at all.

Belief without blindness, effort without illusion — that’s how belief becomes system

This balance sits at the core of Hagen Growth. I believe that we can all create lasting change, but only when we face reality honestly and work with it, not against it. That’s what positive realism teaches: belief without blindness, effort without illusion – it’s how belief becomes system

But even the strongest belief collapses when we chase shortcuts. That’s where most people fall off the path.

Why quick fixes tend to fail

As humans, we’re wired to seek the easiest path to the biggest reward. Biologically, it made sense – conserving energy once meant survival. Our environment changed, but our brains didn’t. That’s why quick fixes feel so appealing: they promise results without friction. But the same instinct that once kept us alive now keeps us stuck.

Quick fixes look efficient, but what comes fast usually fades just as fast. When I was in high school, a parent in my circle would start magazine crash diets a few times a year – one or two weeks of eating almost nothing. The scale plunged in the first days (mostly water), but nothing in her routine changed. As soon as the diet ended, the hunger was unbearable, old habits returned, and the weight came back, often with interest.

The same pattern repeats across all forms of quick fixes. They solve symptoms, not causes. They don’t build new habits, systems, or ways of thinking – the things real change depends on.

The mindset that seeks shortcuts often becomes the very thing that prevents progress. Growth built on illusion collapses as soon as effort stops.

Summary: Positive realism – the foundation of Hagen Growth

- Realism sees the world as it is – positivity believes it can be improved.

- Together, they create a mindset where optimism meets structure.

- The positive brings intent. The realism builds conditions – systems, effort, and time.

- Without balance, optimism becomes illusion and realism becomes paralysis.

Quick fixes collapse because they promise change without foundation. Real growth builds on both truth and persistence.

The Hagen Growth Loop

Ever noticed how one good week makes the next easier – and one bad week makes the next harder?

When I moved to Thailand last year, I stopped training for a while to save energy for my new job – and almost immediately, I started losing trust in myself. Then I began neglecting Hagen Growth. From there, things only got worse. My habits slipped, my energy dropped, and my mindset followed. Within a few months, I barely recognized myself – not in how I thought, not in how I acted.

Looking back, I realized something: life moves in loops. What you do shapes how you think, feel, and see the world – and how you think, feel, and see the world shapes what you do. You’ve probably seen it in your own life: when your mindset improves, your actions follow. When your habits slip, your mindset does too.

The Hagen Growth Loop makes this pattern clear: Behavior <-> Mindset, guided by Reflection.

Your behavior reveals who you are. Your mindset defines how you interpret reality. Reflection, most effectively practiced through journaling, connects the two. It amplifies progress when they align and corrects course when they drift apart.

Mindset

Mindset is the lens through which you view yourself and the world around you. It’s the set of beliefs, assumptions, and stories you tell yourself about what’s possible and who you are within it.

To grow, you have to believe that change is possible and realize that you alone can make it happen. That’s where most people get stuck – believing they need proof before they start.

But when you haven’t yet seen proof, it’s hard to fully believe big changes can happen. That lack of belief makes you less likely to take action, blinds you to opportunity, and keeps you stuck.

As your mindset recalibrates to align with the direction you want to move, it lowers the friction of doing the right behaviors. When your mindset shifts, it changes what you pay attention to, what you attempt, and how you interpret the results. Each action then feeds back into your beliefs, strengthening the loop that moves you forward.

Behavior (habits)

Behavior is the physical expression of who you are. It’s the sum of the actions you repeat – the accumulation of your daily choices. You’re usually aware of what your actions achieve, but not of how deeply they shape your internal world.

What you do determines how you see the world. If you work out, your mind starts to recognize possibility and control – you start to see yourself as someone capable. If you stay inactive and scroll in bed, you reinforce helplessness. Every behavior is a small signal to your brain: this is who I am.

Habits shape your visible life, but their reach is deeper. They create the feedback that forms your mindset. Every repetition strengthens an identity loop: behavior builds belief, belief shapes behavior. When the two align, effort becomes lighter – progress feels natural. When they conflict, friction grows, and the loop turns against you.

Reflection

Mindset and behavior operate automatically, whether you put in effort or not. Every moment feeds the loop – even inaction. Reflection is the act of stepping back to observe how your thoughts and actions interact. When the process runs unconsciously, negative habits or limiting mindsets can take hold quietly. They often appear harmless, sometimes even productive. But over time, they compound into something that limits you.

Reflection interrupts this automatic process. It forces awareness, showing how your actions shape your thinking and how your thinking shapes your actions. Through it, you see where the loop drifts off course and where it gains strength. Reflection doesn’t just help you adjust, it also amplifies effort. Recognizing progress reinforces it, making positive loops stronger and more stable.

The most direct way to practice reflection is through journaling. Writing gives structure to thoughts that otherwise stay abstract. Once on paper, patterns become visible, and progress becomes measurable. This clarity builds what most people lack – perspective. It also shortens the delay between changes in behavior and mindset, allowing both to move in sync.

Reflection turns experience into direction – it’s how the loop becomes conscious

The three functions of reflection

Within the Hagen Growth Loop, reflection performs three important roles:

- Detection – noticing misalignment between mindset and behavior before it compounds. You identify where intention and action don’t align and where energy leaks from the system.

- Interpretation – understanding why the misalignment exists and what sustains it. This is the analytical step: linking cause, emotion, and habit so that correction targets the reason behind it, not the symptom itself.

- Adjustment – realigning the system through deliberate change. Small corrections close the gap between how you think and what you do, preventing the drift from becoming a downward spiral.

Together, these three functions move the loop from unconscious to conscious – turning passive experience into deliberate growth.

How it all ties together

When all three interact, they form a feedback system that constantly shapes your growth – for better or worse. The direction depends on the alignment between what you do, how you think, and how actively you reflect.

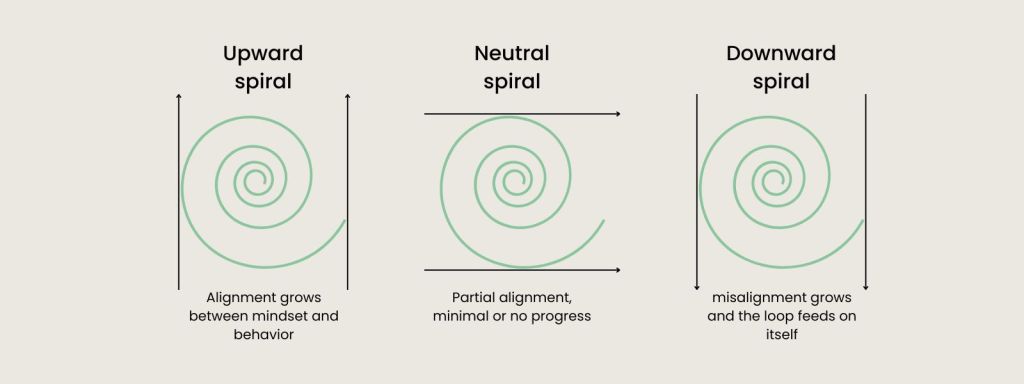

The Behavior <-> Mindset loop runs automatically and creates momentum, either upward or downward. Because the change is gradual, it often feels like you’re standing still – but the loop is always moving.

- Upward spiral: alignment grows between mindset and behavior. You feel stronger, your outlook improves, and your habits start to reinforce your goals. Progress compounds quietly until it becomes obvious.

- Downward spiral: misalignment grows. You feel worse, discipline fades, and destructive patterns replace productive ones. The loop feeds on itself until you intervene.

- Neutral spiral: partial alignment, minimal progress. You’re not declining, but not improving either – just spinning at the same point. Most people stay here for years, confusing comfort with stability – it’s become the modern norm.

You’ve likely felt all three at different points in your life – rising with momentum when things are great, slipping backwards when things are already challenging, or just hovering in one place.

After spending my first months in Thailand caught in a downward spiral, and the rest of the year stuck in a neutral one, I finally managed to turn it around. I started cycling again, just to challenge myself, and as I pushed through discomfort here, I slowly began to trust myself again. From there, both my behaviors and mindset started improving fast, until I began to feel and act like my usual self. When I reflected on it later, I realized something important: even the smallest action can be enough to shift the entire situation – the entire direction of the spiral.

Guiding the loop with reflection

Reflection is what changes the loop from unconscious to conscious. By catching patterns early and adjusting before they compound, you stop regression and accelerate alignment. Reflection lets you step outside the loop, examine it, and re-enter with control.

When you practice it consistently, the loop becomes conscious – something you shape, not something that shapes you.

How to apply it in real life

Most people run the loop unconsciously – reacting instead of guiding. The goal here is to flip that dynamic.

Understanding how the Hagen Growth Loop works is one thing, applying it is another. To turn the concept into real change, I’ve defined four steps that move the loop from automatic to deliberate, a practical way to direct your life instead of being pulled by old patterns.

The first time you use it may feel slow or awkward, but it gets easier. Over time, reflection and adjustment become instinctive – the loop starts working for you instead of against you.

The four steps below are the conscious counterpart to the unconscious loop. They show how to use awareness and small, deliberate actions to take control of your growth.

Most people run the loop unconsciously – growth begins when you start guiding it

1. Identify the current situation

Before you work with the loop, map where you are now. Look at three things:

- Mindset: What assumptions and stories are running? What do you believe is possible?

- Behaviors: What do you actually do most days? What repeats without effort?

- Interaction: Where do beliefs and actions reinforce each other? and where do they clash?

You also determine which spiral you’re in – upward, downward, or neutral – and how fast it’s moving. This analysis builds the foundation for every later correction. It exposes patterns that normally stay hidden and strengthens the self-reflection skill the rest of the process depends on.

This step matters most the first time you work consciously with the loop, but it should never be skipped. After every five to ten cycles, or after any major shift in your life, revisit it in full depth.

2. Reflect before change

Once you’ve mapped your current loop, look for points of friction – where your mindset and behavior pull in different directions or fail to move you where you want to go.

There are two ways to push the spiral upwards:

- Remove negatives: Let go of destructive habits or limiting beliefs. Doing so stops downward momentum and creates space for alignment.

- Reinforce positives: Build or strengthen the habits and beliefs that move you forward. This is how an upward spiral gains speed.

You can enter from any side of the loop – mindset, behavior, or reflection itself. Each entry offers different advantages.

The best place to start is where resistance is lowest and action feels simplest. The goal is to create momentum – big changes will follow as momentum accumulates.

3. Adjust

After spotting what needs to change, adjustment is where it happens. It doesn’t come from big leaps but from small, deliberate shifts in either mindset or behavior. The smaller the step, the easier it is to maintain – and the clearer the feedback becomes. You’ll quickly see what works, what doesn’t, and what needs refining.

Once one side of the loop shifts, the other naturally follows, or is easier to change. The scale of the adjustment determines how long each cycle takes. Micro-adjustments move fast. Larger shifts need time to stabilize. For most, a week is enough for one full cycle before adding another small change or increasing intensity.

4. Reflect after change and repeat

After change, reflection closes one loop and begins the next. How often you return to it depends on the scale of your adjustment – small changes can be reviewed weekly, larger ones require more time.

Here, reflection shifts focus. In step two, you reflected to plan direction, now you reflect to measure effect. Look at what changed, how it felt, and how it influenced your spiral. Did the shift move you upward, downward, or keep you still?

The purpose is not judgment but awareness. Most results appear gradually, as small gains compound through consistency. Reflection makes those patterns visible and helps you decide whether to stay the course or adjust again.

Each cycle strengthens clarity and control. Over time, this repetition turns conscious effort into an automatic way of operating – the loop starts to guide itself.

Summary: The Hagen Growth Loop

- Mindset and behavior constantly shape each other, creating either progress or regression.

- Reflection turns the loop from automatic to conscious – it’s how you guide growth instead of reacting to it.

- Alignment between thought and action builds upward spirals – misalignment pulls them down.

- Apply the loop through four deliberate steps:

1. Observe – notice your current loop.

2. Reflect – identify what’s driving it.

3. Adjust – align behavior and mindset.

4. Repeat – build momentum through consistency.

The Hagen Growth Loop reminds us that direction matters more than speed – every deliberate adjustment shifts the spiral.

The principles behind growth

The Hagen Growth Loop explains how change happens – it’s the mechanism behind growth. But to make growth last, the loop needs support. It needs principles that keep it stable, even when progress slows or life gets difficult.

Five principles make growth sustainable and an integrated part of your life – the foundations that keep the loop moving upward, or at least neutral, when momentum fades:

- Self-awareness

- Systems

- Small wins

- Discipline

- Minimum viable output

Self-awareness

We have to understand what we’re doing and how it’s affecting us. Without that awareness, it’s almost impossible to make the right adjustments or sustain growth.

Self-awareness means seeing yourself clearly – knowing what you want and why you want it, how you feel and why you feel it. It’s an understanding of who you are, what you do, and how your inner state and actions shape each other.

While no one has full awareness all the time, a strong sense of it is essential. It sits at the center of reflection in the Hagen Growth Loop. It helps you see which beliefs move you forward and which hold you back, acting as the guide that lets you evolve deliberately rather than repeat unconsciously.

Most of us overestimate how much awareness we have. But like any skill, it can be trained. Deliberate practices – whether mental or physical – strengthen your ability to notice what’s happening beneath the surface, allowing you to respond with clarity instead of impulse.

Systems

Systems, routines, and procedures are the backbone of sustainable success – whether in business or in personal growth. Nothing lasting comes from sporadic effort. Without systems, every action needs a decision, and two problems appear:

- You give yourself the option to quit every time something feels hard. Most people will take it.

- Each decision costs mental energy. The more choices you face, the more fatigued you become, and the easier it is to make poor ones.

That’s why systems matter. They reduce friction and conserve energy for the work that actually moves you forward.

How you design your systems depends on your nature – some need rigid schedules, while others need flexible frameworks. But whichever you are, structure isn’t optional. Fixed workflows, preplanned workouts, and consistent routines remove unnecessary decision-making and make progress predictable. Systems don’t limit freedom, they create it by freeing your attention from what doesn’t matter.

Small wins

You don’t need a breakthrough to change. You need proof. Small wins are those quick, undeniable proofs of who you’re becoming.

Small wins have been part of Hagen Growth from the very beginning – both in my own journey when I went to the gym for the first time and in the philosophy that shaped this platform. They are the small moments of success that reinforce who you want to become.

A small win happens any time you do something good for yourself or resist something that pulls you away from your goals. It usually takes one of two forms:

- Taking action: Completing a workout, choosing a healthy meal, sitting down to write, or simply making your bed.

- Holding the line: The moment you don’t give in – when you skip the cigarette, resist the junk food, or face boredom without reaching for your phone.

The more a win aligns with the identity you’re building, the stronger its effect. But even the smallest wins count. We often overlook them because they feel insignificant, yet they’re what keep the loop alive during the slow, invisible parts of growth. Each small act compounds into momentum.

Discipline

Without discipline, every good idea dies at the first feeling of resistance. You need it to resist cravings, to start your work, to eat well, to push for one more rep, and to put your phone away when it’s time to sleep. You even need it to hold your mind steady when doubt and negative thoughts try to take over.

Discipline isn’t fixed. Many think it’s something you’re born with, but like any skill, it can be strengthened through use. Discipline and willpower function like a muscle: the more often you resist temptation or choose the harder action, the stronger they become.

But discipline alone can’t carry you. Like any muscle, it weakens with overuse. If you depend on it for everything – every choice, every behavior – fatigue builds and failure follows. That’s why systems matter. Systems preserve energy and make good decisions automatic, so discipline is used only where it truly counts.

Minimum Viable Output (MVO)

Life is unpredictable. At times, you’ll be thrown off balance – by illness, stress, major change, or instability. During those periods, expecting yourself to perform at your highest level is unrealistic. Pushing through can turn pressure into collapse. I’ve learned this the hard way.

The minimum viable output (MVO) is a strategy to prevent that collapse. It defines the smallest version of your habits and systems that keeps momentum alive without burning you out. It’s not about progress – it’s about preservation. Because restarting from exhaustion is always harder than scaling up again.

When you enter MVO mode, the goal is simple: stay in motion. Keep habits alive, maintain identity, and meet essential commitments – even if everything else pauses.

How change becomes identity

Real change isn’t complete when you can do something – it’s complete when you no longer have to think about doing it. Growth begins as effort, but ends as identity. The tools, systems, and principles that once required deliberate use eventually become natural parts of how you live.

The first time you practice a new behavior, it feels forced. The second time, slightly easier. By the tenth, resistance fades. That early friction comes from misalignment between your current identity and the person performing the new action. Each repetition brings them closer together until the effort dissolves – the habit feels natural, and identity has shifted.

Growth begins as effort but ends as identity

The principles above are only tools until then. They guide you through the early, deliberate phase of change – but their real purpose is to disappear, to become part of who you are and how you naturally operate.

The process of identity change

Identity change follows a consistent sequence – the same five stages occur whether you guide them or not. The difference lies in awareness: when conscious, the process builds growth deliberately. When unconscious, it shapes you.

1. Awareness

You begin by noticing misalignment – between how you think, act, and see yourself, and the version of you that could exist. This recognition creates internal tension, the productive discomfort that drives change. Without that tension, there’s no reason to move.

2. Small action

You take small, controllable actions that prove change is possible. The mind trusts evidence more than intention. Each small act becomes proof of capability – a signal that a new identity can form.

3. Reflection

You review what worked, what didn’t, and how it felt. Reflection converts experience into understanding and prevents blind repetition. It keeps your effort aligned with the identity you’re building.

4. Adaption

You refine systems, environments, and beliefs based on those insights. Adaptation turns temporary effort into stable progress. It’s what makes change sustainable instead of situational.

5. Identity reinforcement

Aligned repetition rewires belief. The brain starts saying “I am” instead of “I try.” What once felt like effort becomes self-expression – an integrated part of who you are.

One morning I opened my calendar and started exactly where the day’s first task began. Months earlier, I would have jumped between tabs, checked metrics, and spent an hour deciding where to start. Now it was instinct: open the calendar, check the plan, do the work. What once caused friction now felt natural. Structure had stopped being effort – it had become the way I work.

The Hagen Growth Loop always runs. The difference is whether you guide it consciously or let it define you

The negative loop

The same process that builds growth can also build stagnation or regression. The difference lies in awareness. When the loop runs unconsciously, it reinforces the identity you didn’t choose.

1. Blindness instead of awareness

Destructive patterns always leave traces, but without awareness, they go unnoticed. Neglect, avoidance, or denial allows them to take root quietly.

2. Avoidance instead of action

Rather than confronting discomfort, you retreat from it. Each avoided task or postponed decision reinforces passivity and makes future effort harder.

3. Rationalization instead of reflection

Instead of examining why something failed, you explain it away. Responsibility shifts outward – to circumstances, timing, or others – and the chance to learn disappears.

4. Resistance instead of adaptation

You defend the familiar even when it holds you back. The same beliefs and habits that caused the problem become the walls that keep you in it.

5. Identity erosion instead of reinforcement

Over time, the story turns inward. You start believing you’re the kind of person who can’t change – lazy, inconsistent, incapable. The deeper that belief settles, the harder it becomes to escape. Awareness is what breaks this spiral. Without it, the loop completes itself by default.

Summary: The Hagen Growth Loop

- Real growth begins as effort but ends as identity – what once felt forced becomes who you are.

- Each cycle of action, reflection, and adaptation rewires self-image through evidence, not intention.

- When awareness fades, the same process builds the opposite: stagnation, avoidance, and self-doubt.

- Awareness is the difference between a loop that shapes you and a loop you consciously shape.

Growth isn’t accidental or sudden. It happens gradually over time, shifting your identity as you go.

The vision

The philosophy above explains how growth happens – how small actions, reflection, and awareness shape identity. But philosophy alone isn’t the goal. The purpose is to build a life that feels deeply meaningful and true.

Hagen Growth exists to make that kind of life possible – a life rooted in calm realism, steady effort, and alignment between what you value and how you live. It’s not about chasing endless improvement. It’s about cultivating stability and direction, so every action carries purpose.

To live by this philosophy is to find peace in motion: to work hard without restlessness, to grow without losing balance, and to see effort itself as part of what makes life meaningful.

The life Hagen Growth is trying to build

The life this philosophy points toward is calm but alive. It values consistency over intensity, awareness over control, and depth over distraction. You accept where you are, but never stop moving toward who you could become. Systems and discipline give structure; reflection and awareness give depth. Together, they make life both steady and vivid – shaped by meaning rather than momentum.

This isn’t a life free from struggle. It’s a life where struggle has context. Where effort isn’t something to escape, but something that defines you.

Where Hagen Growth is heading

Hagen Growth is growing by the same principles it teaches – through steady iteration, lived experience, and deliberate refinement. This philosophy isn’t just a static document – it’s being practiced in real-time. You can follow that process on social media, where I document the journey of finding meaning and testing these principles in everyday life.

On this site, the work continues to expand into a library of deep-dives and practical tools. Each entry explores a specific part of the system – from mindset and structure to identity and behavior – making the process of deliberate growth more tangible.

Over time, this will form a complete framework that others can use to shape their own path – a system built not from theory alone, but from practice, awareness, and honest iteration.

Every tool, guide, and resource builds on the same foundation: awareness, structure, and meaning. The goal is simple: to help more people live deliberately, not perfectly. To remind them that growth isn’t something you chase. It’s something you build, one deliberate act at a time.

- Mindset and Discipline: The Foundation of Sustainable Change - March 4, 2026

- Thinking Vs. Reflection – What is the difference? - February 20, 2026

- Why we do things we later regret – and how to interrupt the pattern - February 13, 2026